One spring, when my son was in elementary school, he decided that we needed to build a birdhouse. We worked together on it – designing the house, figuring out what the parts needed to look like, buying the wood and other materials, and constructing the house. Gregory painted it, and we hung it outside our breakfast room window.

Then we waited. Birds came and birds went, but none moved in. One day, Gregory said to me, “Dad, I don’t think the birds like our birdhouse.”

He was right! We hadn’t considered the birds. When we did some research, we found out that birds are very particular. Different birds have different preferences – as to size, location, the size of the entry hole, etc.

I was chagrined. We built this birdhouse at a time when I was managing a Customer-Centered Innovation Group at a Fortune 500 company. And I hadn’t even considered the “users.” It struck me how easy it is, in the press of trying to get innovation done, to forget the customers.

Users need to be the touchstone of any innovation process that seeks to introduce something new into their world. Their involvement needs to be deep, continuous and interactive. A focus group here and there won’t do.

Tools I have found useful depend on the stage of the innovation effort. In the early stages, when needs are being identified, ethnography is valuable. An ethnographer goes into the world seeking to understand it from the point of view of its participants. The field started with anthropologists studying foreign cultures, which is fitting because the worlds of our customers are often foreign to us – with their own languages, artifacts, relationship networks, reward structures and ways of working. A key discipline of anthropologists is to leave any preconceptions at the door. This can be difficult, especially for technical professionals.

Once ethnography has helped to uncover needs, the ideas will flow quickly. Immersing yourself in another world is generative. Prototypes are a great way of continuing the interaction with potential customers. There are many different types of prototypes – those that probe the need and help to validate (or invalidate) it; those that embody a full value proposition; those that test the interaction with a user; and those that test the technology in use in the customer’s world. In each of these, the customer is the touchstone. An innovator needs to be clear about the purpose of a prototype and design it to clearly answer the question at hand.

For each variety of prototype, customers have let me know when I was off track. A very simple prototype probing the need for a secure folder – a hand-drawn prototype built in 20 minutes – clarified that users were interested in privacy, not security (a very different need). A functional prototype we built for a law firm demonstrated that the digital filing system we thought they needed just didn’t create the value either of us anticipated. And a third prototype, which designed cements for oil field engineers, met an important need but didn’t fit into the way the engineers did their jobs. That experiment helped me to understand that the social context of a technology can make or break it. In each of these cases, the prototype prevented us from wasting a lot of time and money delivering products that people didn’t want or couldn’t use.

Engineers and technical staff are often reluctant to get out of the lab and interact with end users. Creators (of all types) can be reluctant to expose their concepts until they have been perfected. The whole process takes people out of their comfort zones, and it can be tempting to delegate the customer insight task to surveys or to the marketing and sales departments. But there is no substitute for being there. I have never seen an innovative mind interact with a new customer world and not generate ideas.

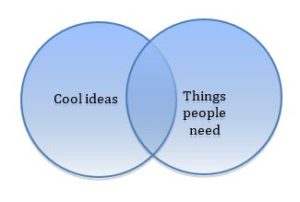

I sometimes think in terms of a Venn diagram illustrating two approaches to innovation. People often start in the left circle, with a great new technology or concept. They refine the concept and then begin the frustrating search for customers who might be compelled by it. This is looking through the wrong end of the telescope. It is far easier to start in the right circle, with customer needs. It is rare that good engineers cannot invent solutions to well-defined needs.

In practice, being customer-centered is harder than it seems. We all fall in love with our ideas and are drawn to refining them. We get lost in the excitement of making the birdhouse and forget all about the birds.

Learning from users is what the Value Hypothesis in Lean Startup is all about. Read how to make this work in the corporate context in my book, Lean Startup in Large Organizations: Overcoming Resistance to Innovation. Available at Amazon and http://leanstartup.biz/.

Recent Comments